I know what this is. I see it before me. I can feel its presence. I want it gone now. I will keep writing though. I will not give up. I know it wants that.

I realize it can be hard these days to tell what is real and what is machine made, but that, up there, is human writing. What makes it sound odd and stilted is that it was written under the influence of the anti-muse. Maybe you think that a visit by the anti-muse would mean that you cannot write at all, that you would be crippled with writer’s block, but that is not always the case. Sometimes when the anti-muse comes, you can still write, you just can’t write good.

When the anti-muse came to me it hid itself inside my really, really good idea. It likes to hide because it doesn’t want you to know that it is in-house. Like the killer in a horror movie, the anti-muse will go as long as it can before you get the shock of finding out that the calls you think are coming from the outside are actually coming from within the house, something much scarier in the years before cell phones. However, it is still scary to think that what you thought was your brain functioning independently was really a brain under a stealth attack by the anti-muse.

Anyway, this was what I wanted to write, something like: Dante and Me—The Same In Almost Every Way.

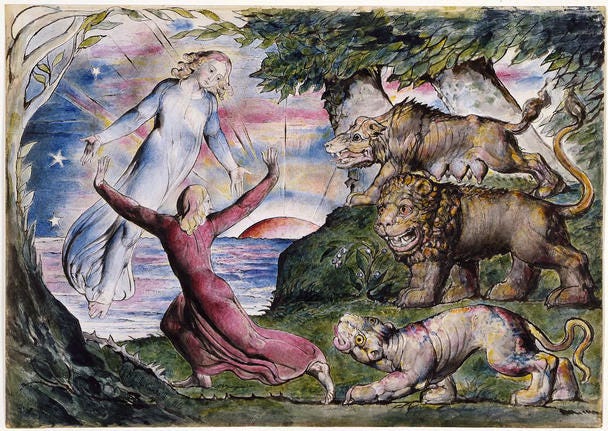

I was going to write about how we both found ourselves in the middle of our lives lost in a dark wood, also, how we were exiled from our former lives, and how some of our favorite writers, or literary characters or heroes from the past came along to help as guides. And, of course, the thing I wanted to highlight the most, the best thing we shared in common: we both like to write, and mostly about the same thing—the dark wood.

There was so much material I could’ve written a book, or maybe even a three part epic poem about it. I got going and was already hard at work when it showed up. At first, I thought it was the regular muse because that’s what a normal muse does, it shows up and things begin to happen. But this time I totally misread the signs. Typically when the muse comes, which is only when it feels like it, it is good to be seated at a desk ready to go—which I was. So when the anti-muse came instead I failed to see it because I was too busy being grateful that I was in position to write. I should’ve known something was up because normally, when the muse shows up, I am far from my desk and nowhere near a writing implement. These days I no longer let that stop me and will make my own writing implement if I have to. Did you know that the Egyptian god Thoth was the one who pushed for writing things down? I am all for that, even though Plato thought it would cause problems down the road with our brains because we wouldn’t remember as well or something like that.

Sitting at my desk, writing away, I thought, based on the flood of ideas coming to me, that the muse was at hand. But after toiling for hours, something felt off. I had ideas, just no words to express them with.

Worse, I could barely write a sentence. What I did manage to write, after a long struggle session was horrible. I had about ten little, deformed five word sentences that, for some reason, had to start with I as if they had been written by a mono-syllabic, single cell organism—me want, me say, me go.

Sadly, after all that time spent “crafting” sentences the words refused to hang together. This was because they couldn’t hang together, they couldn’t do anything because they were all dead. Shot dead by the anti-muse which hid inside my Dante idea, pretending to be a regular muse and yet, unlike one in every way.

Normal muses are mercurial and erratic, but when they do arrive they like to get right to work collaborating and playing. Which to them is the same thing. The anti-muse, on the other hand, is all work, zero play, and pathological about never taking breaks. Unlike the muse who is quick to come and go, the anti-muse has all the time in the world (which was actually my time) to wait. And wait it did for each thought to emerge so it could, in that space between my brain and the keyboard, shoot its venom, stunning the words mid-flight so that they fell to the ground with a thud. All my lovelies—killed.

And not just my lovelies but some of Dante’s too. I don’t know how this is possible—Dante’s own writing shot down dead because it had the temerity to go through my brain and get mixed up with my words.

That was when I knew it wasn’t Dante, it couldn’t be, he’s Dante. But it also wasn’t me, I am definitely not mono-syllabic or single-celled. And it certainly wasn’t the muse, muses aren’t mean like that. It had to be the anti-muse, which, if you’re interested, acts like a wasp, not the Mayflower-arriving WASP, the insect kind, but with a strong Puritanical work ethic.

I hate this anti-muse because it hates me. Because it won’t let me have nice things like Dante. Because it wants me to give up, to walk away defeated. But I won’t, even if it takes a tortured hour and a half to produce just one five letter sentences. And even if seeing those sentences together, the way they are all lined up like soldiers on a death march led by the I, makes me want to throw up.

What is happening? I ask.

But the question I should ask is: Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

I thought my verse was alive, but maybe it just looks alive, like Fra Albergio, someone Dante runs into in hell:

“Oh, said I to him, are you already dead?

And he to me: I have no knowledge

how my body fares in the world above.

Dante believed Fra Albergio to be alive because he had just seen him walking around, doing normal things like eating and drinking and putting on clothes, but the shade corrects him, what Dante had actually seen walking around was the effigy of the man, the real man was dead and in hell:

Know that the moment when a soul betrays

As I did, its body is taken by a devil,

Who has it in his control

Until the time allotted it has run.

How awful. But then again, there were my words, also under some kind of control doing the same thing--pretending to be alive.

And that is the anti-muse’s plan: to separate me from the act of writing by taking the life out of it. It wants me to no longer seek the connection writing provides, not just to the people I know, who know me, but to people who were never even alive at the same time as me. Or, the characters that were not confined to flesh and blood bodies or even the stories they originated in. All of them, in whatever state of existence, who continue to impact those of us lucky enough to find them, like me finding Dante. I never met him, but I know him and he, somehow, knows me.

According to the anti-muse, this wisdom that I have available to me, the counsel of these great figures is not to be countenanced. The anti-muse will not permit it, instead it wants me to believe this:

Dante cannot help you, no writer can. You will remain stuck in your own selva oscura, lost and alone.

But the anti-muse made a bad mistake in leaving me alone in the dark wood because it is there where I encounter Dante face to face, in the present, and he not only lives, he speaks.

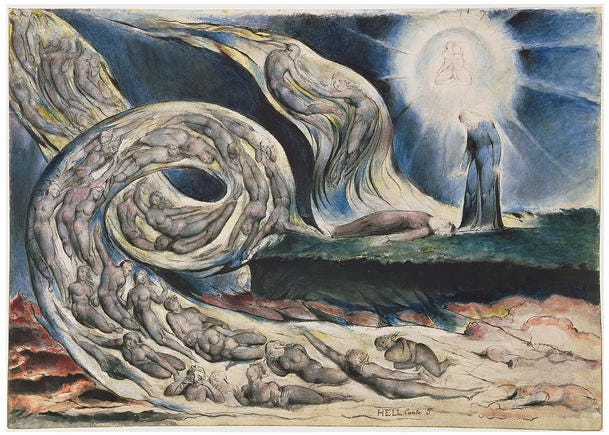

He tells me what he knows, like what it is to be afraid, and what it’s like to go around and around ad infinitam, or what it is like to be chased and stung by a swarm of wasps. He describes everything and even has a name for it, Inferno.

But these tortures are not for him, they are for the souls trapped there.

How much the anti-muse would like you to think that you too are stuck, immobile as those unfortunates in the ninth circle of hell. But, like Dante, with the help of Virgil, you also can find a way out.

The anti-muse can do a lot of things, it can run interference, it can put on a show, it can paralyze any writing. But it knows that even with all its trickery it cannot do what every human who has ever written can do— it cannot create.

Poiesis is what the Ancient Greeks called it. Poetry we call it now. But it is bigger than a poem. It is the living, moving act of making something out of nothing— nothing except the material of one’s own life.

Consider well the seed that brought you forth: you were not made to live your lives as brutes, but to pursue virtue and knowledge.

When Ulysses needed to rally his troops he spoke those words to remind them who they were and what they were charged— no, rather, made to do.

I go back to look at what I have written.

It appears that the words I thought were dead, were just pretending to be dead. And unlike Fra Albergio who actually was dead but pretending to be alive, these words of mine were simply waiting for me to touch them, and with a nod from the muse, make them into something new.

This issue of Suffering School is my new favorite, probably because you've explored territory here that is painfully familiar to me, masochistic as that sounds. As always, your writing is smart, funny, and vulnerable in equal measure. Those "wasps" you referenced here - nice metaphor, BTW - have been stinging me for as long as I can recall. Keep on writing; I'll keep reading.